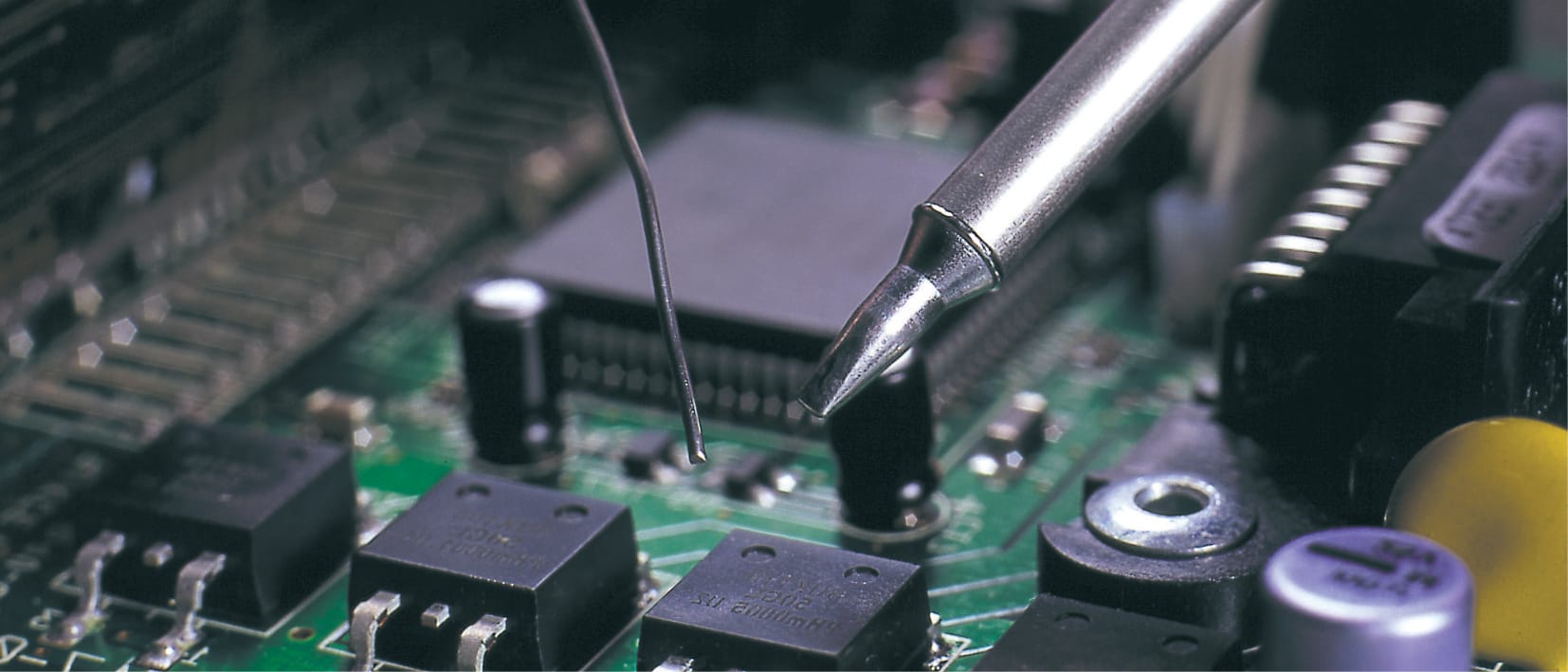

1.1.8 Thermal Joint: Soldering

Soldering joins metal parts with a molten filler metal rather than melting the base material of the part. Solder is typically a tin or lead alloy that melts at temperatures below 350°C (662°F), causing less thermal stress than welding. Melted solder is drawn by capillary action between metal surfaces. It is electrically conductive, suitable for small parts and may be reworked at relatively low temperatures, which makes it a popular choice for electronics.

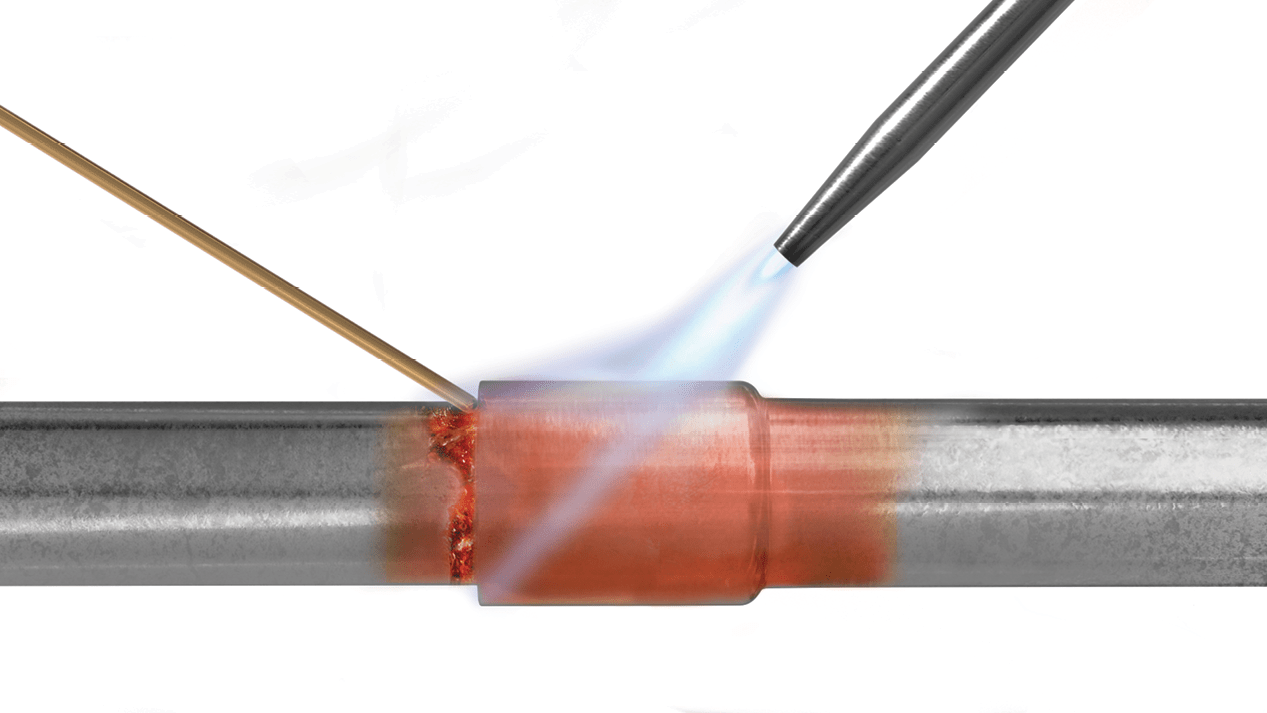

1.1.9 Thermal Joint: Brazing

Like soldering, brazing does not melt the base metals. Brazing temperatures are higher than soldering, ranging from 450°C (840°F) to 800°C (1,470°F) for hard brazing. Brazing creates a metallurgical bond between the filler metal and the surfaces of the two metals being joined. Heat is applied broadly to the base metals; when the filler metal is brought into contact, it is melted and drawn by capillary action through the joint.

The most significant advantage of brazing over welding is that the base metals are not melted, so they can retain most of their physical properties. Base metal integrity is a characteristic of all brazed joints, including thin- and thick-section joints. The lower heat also minimises the danger of metal distortion or warping.

Brazing offers a significant advantage in joining dissimilar metals, including copper and steel, as well as non-metals, such as tungsten carbide, graphite and diamond. A properly brazed joint, in many cases, could be as strong or stronger than the metals themselves.